Saying the deal would create a “publishing behemoth,” the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice filed an antitrust lawsuit on Nov. 2 to block the world’s largest publisher, Penguin Random House (PRH), from acquiring rival Simon & Schuster (S&S). A combined company would be able to “exert outsized influence” over which books are published and how much authors are paid for their work, the suit alleges.

The publishing industry is already highly concentrated, largely controlled by the “Big Five” publishers. PRH (which owns Knopf Doubleday and others) is the world’s largest book publisher and S&S (which owns Scribner, Pocket Books, the Folger Shakespeare Library, and others) is the fourth largest U.S. book publisher. PRH, a subsidiary of Germany’s Bertelsmann SE & Co., publishes 2,000 new trade books in the U.S. annually, generating $2.4 billion in 2019. S&S, owned by ViacomCBS Inc., publishes 1,000 new trade books each year, reporting 2019 revenues of $760 million. The other big U.S. publishers are Hachette Book Group, which includes Little, Brown & Company and is part of a French conglomerate; HarperCollins Publishers, a subsidiary of Australian media mogul Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp; and Macmillan Publishers, which, like PRH, is owned by a German parent company.

The Big Five compete to acquire manuscripts and pay authors advances for the rights to publish their books. In most cases, the complaint alleges, the advance is an author’s total compensation for their work. A writer’s best chance to make money is to get an advance from one of the Big Five. Smaller publishers can and do offer lucrative book deals but operate at a distinct disadvantage against the top players. Should it go through, the merger would reduce the Big Five to four and put the new company in control of close to half the market, the government says. This would leave “hundreds of individual authors with fewer options and less leverage.” The complaint alleges that PRH itself sees the publishing market as an oligopoly, and said it intended to acquire its rival to “cement Penguin Random House as #1 in the U.S.”

In a statement accompanying the complaint, the government said the Antitrust Division’s Horizontal Merger Guidelines “lay out a straightforward framework to analyze monopsony cases, and under those guidelines this transaction is presumptively anticompetitive.” Monopsony occurs when only one or only a few buyers are present in the market. A monopsonist possesses the economic power to depress prices below the competitive level in order to pay less for necessary inputs.

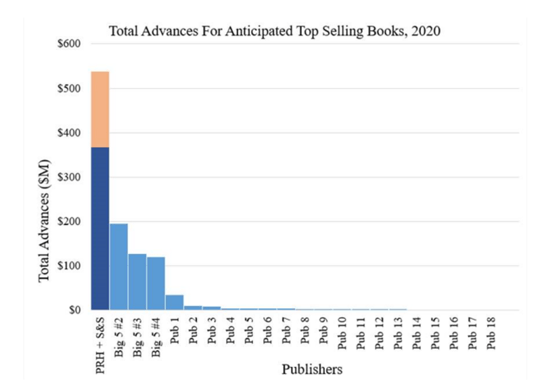

The complaint included a graph (below) showing the level of advances each publisher would pay to authors should the merger occur. The merged entity would gain control of nearly $550 million in authors’ advances, more than the next three competitors combined.

PRH and S&S have vowed to fight the lawsuit, appointing nationally recognized trial attorney Daniel M. Petrocelli of O’Melveny & Meyers to represent them. Petrocelli successfully defended AT&T and Time Warner against the Justice Department’s failed attempt to block their $100 million merger.

Publishers: Deal is good for competition.

In a joint statement from the publishers, Petrocelli said, "DOJ's lawsuit is wrong on the facts, the law, and public policy. Importantly, DOJ has not found, nor does it allege, that the combination will reduce competition in the sale of books. The publishing industry is strong and vibrant and has seen strong growth at all levels. We are confident that the robust and competitive landscape that exists will ensure a decision that the acquisition will promote, not harm, competition."

The publishers justified the acquisition by saying it “will bring PRH's superior order fulfillment services to S&S's titles, benefiting consumers by making it easier to discover new titles and less likely that books will be out of stock, particularly at local retailers. Beyond the benefits to consumers, PRH's reach into independent bookstores and specialty markets will boost the sales of S&S titles, benefiting both authors and retailers.”

Calling the publishing industry “highly competitive,” PRH and S&S said they have many competitors, including “large trade publishers, newer entrants like Amazon, and a range of mid-size and smaller publishers all capable of competing for future titles from established and emerging authors.”

According to statistics compiled by Statista, in 2020, the estimated net revenue of the U.S. trade book publishing industry amounted to $16.67 billion, up from $16.23 billion in 2019. “Revenues have been creeping up each year since 2013, and five years of steady growth has led to an overall increase of more than $1 billion in that period,” Statista reports.

Is consumer harm really necessary in this case?

All successful antitrust prosecutions require a demonstration of harm to competition in a relevant product market. Here, the Antitrust Division alleges the relevant markets to be two “content acquisition markets,” in which authors sell the rights to their works (one market for general-interest works and the other for best-sellers). The harm to competition that occurs in those markets is borne not by book-buying consumers but by the sellers of content—the authors.

This does not mean that consumers are not likely to be harmed by the merger. Rather, it means that the retail book market would not be directly harmed by the merger. If, as the complaint alleges, the merger will reduce competition for authors’ works, consumers will suffer from less efficiency in book publishing and fewer new book titles published each year.

We suspect that Attorney Petrocelli knows very well that the government is required neither to allege nor prove harm to competition in the retail book market. His observation that the DOJ neither finds nor alleges that the combination will reduce competition in the sale of books only serves to distract from the true issue in the case: harm in market for the sale of manuscripts.

Although it may seem counter to popular notions of antitrust, consumer harm in this case is not a necessary element of the offense.

Edited by Tom Hagy for MoginRubin LLP.